At Renewable Energy Malawi (Renama), Kenneth Mtago, 37, is a ‘foot soldier’ rallying communities to embrace energy options that meet present needs without harming future generations’ chances in life. He has been all over Malawi explaining the importance of modern and sustainable energy. However, his shocker came when he visited Traditional Authority (T/A) Mavwere, Mchinji, to count households using energy-saving cookstoves and portable solar products.

Near the border between Malawi and Zambia, he met families still burning firewood and grass for lighting because electricity is beyond their reach and unaffordable. He states: “Having grown up in both rural and urban areas, I find it pathetic that some citizens, especially widows, struggling to raise orphans singlehandedly, are still using firewood and straw to find their way in the night.

“As they cannot afford a solar-powered lamp or anyform of clean energy, they frequently suffer diseases caused by inhaling smoke and fumes from burning firewood and crop residues for cooking and lighting. “Clearly, national programmes meant to lift the poorest of the poor out of poverty are not reaching those who cannot fend for themselves.” Mtago, advocacy officer at Renama, is worried that just over a tenth of the country’s population has access to electricity.

“It shows the country is failing to provide life-changing services, including modern energy, to citizens in danger of being left behind in national efforts to end poverty,” he says. In 2015, President Peter Mutharika and other world leaders adopted the sustainable development goals (SDGs) to end all forms of poverty by 2030.

In SDG7, the 17-point global agenda demands bold efforts to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable energy for all—the backbone of the revised National Energy Policy Cabinet adopted last year. However, the 2018 census shows progress to end energy poverty remains slow.

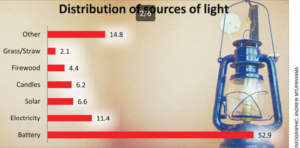

According to the national dashboard, the number of households using electricity rose by just one percent within a decade. It reads: “The battery was the main source of energy used for lighting in Malawi (52.9 percent) followed by electricity (11.6 percent), solar (6.6 percent), candles (6.2 percent) and 4.4 percent of the households used firewood as the main source of lighting.” And 2.1 percent of the population burn grass or straw for lighting.

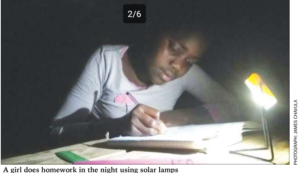

This means that those inhaling waxy smoke and fumes from candles are almost equal to the population burning homes. Schoolchildren in these homes struggle to study and do homework after sunset, falling behind their peers with electricity.

During the global talks on how to scale up energy access and finance in the least developed countries (LCDs) in China, United Nations High Representative for the LCDs, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States Fekitamoeloa Katoa Utoikamanu unpacked the transformative power of modern energy.

She reckons the race against poverty will “largely be wonor lost in least developed countries” such as Malawi. She states: “While all the SDGs are important, goal number seven on sustainable energy is an essential foundation upon which the other goals can be achieved.

“Having access to sustainable, modern, clean forms of energy means that hospitals can fully function, it means that children are not doing their homework by candlelight, it means women don’t have to trek for kilometres to collect firewood or cook in smoke-filled kitchens and it means communities that are empowered to take charge of their own socio-economic development.”

Every week, Louis Richman, a father of three on the banks of Linthipe River in Dedza spends K500 buying dry cells for a torchlight “so that the children can locate their beddings and sleep safely” before the battery runs flat. He narrates: “We switched to the battery lamp three years ago when we realised that paraffin smoke and smells were dangerous to our health.

“As nearly every household embraced the smokeless and smell-free torches, we were spending huge sums and

travelling long distances to buy paraffin. The torchlight is safer than oil lamps which put our grass-thatched homes at risk of burning.”

The battery solution has banished paraffin, but most users find it costly to replace dry cells and less durable

lamps.There are similar concerns with an influx of cheap solar lamps marketed as handy solutions to exclusion from the grid and blackouts.

Yohane and Virginia Chaoloka, commercial farmers in Nkomba in Dedza, use solar power for lighting. The couple fakes discourage people from embracing renewable energy solutions which are cleaner and more reliable than the by dry cells appear cheaper, but a reliable solar system is less costly in the long run. It does not require new battery every week or buying a new one every year,” Yohane says. His wife is fascinated by the clean side of solar light bulbs.

Says Virginia: “In times of paraffin and candles, I was inhaling smoke when cooking and even when chatting with my family before going to bed.”

And Mtago unravels the unclean side of the famous battery lamps. He warns: “The shift is not beneficial. It increases e-waste in form of flat b that can no longer be used and other discarded electronic accessories. Distributors need to offers ways of managing waste products. But the country does not have e-waste policies and facilities.”

Exclusive Report 2019.in2 08/18/2019 10:11:46 AM – by James Chavula-Staff Writer